See it All

by William Pym

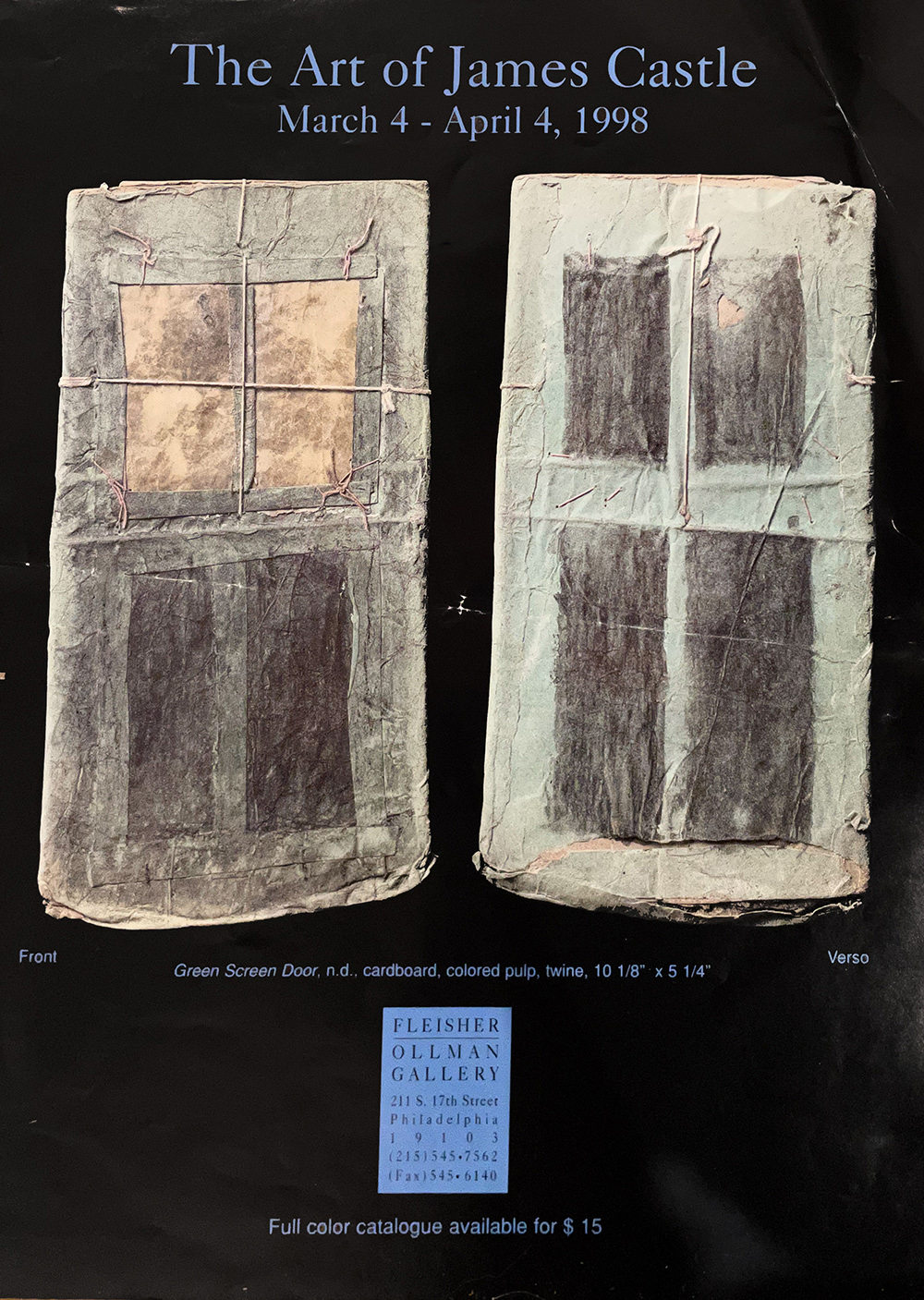

John Ollman started showing James Castle in 1998, one year after the Janet Fleisher Gallery became the Fleisher/Ollman Gallery. John had worked as Fleisher’s director since 1971, and the name change reflected Janet’s retirement from the public face of the art scene. John’s first three decades in the biz had been marked by hard-won discoveries and relentless support; putting his weight behind Castle for the first time represented both a new chapter and a natural continuation of this yeoman’s work.

Postcard for James Castle’s 1998 exhibition at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery.

In gallery shows and at fairs, John and dealer colleagues, mostly women, spread the word in the late ’90s. Everyone showing Castle material had to get patched in to Boise, Idaho, where the archive lived alongside the community of people with stakes in it. Cataloguing and preservation began to accelerate as more people took interest and the estate took on financial and archival structure. It was the right moment. Castle had been known and shown regionally, with two survey exhibitions during his lifetime at the Boise Gallery of Art (now the Boise Art Museum), in 1963 and 1976, but he had never received horizon-to-horizon appreciation in the twenty years of lively outsider discourse since his death.

I was hooked in to the gallery by Brendan Greaves in 2003, who had been hooked in by our more professional friend Jina Valentine, who had joined some months earlier. Castle was buzzing at that time. In our first years, we took countless enjoyable calls about his work with Shari Cavin, of Cavin-Morris Gallery, and Karen Lennox, a vivacious and very chatty dealer in Chicago. We got to show Castle at a lot of classy fairs with righteous open-bar previews. Jina met Oprah Winfrey.

In the early 2000s, Castle’s interiors were the most highly thought-of pieces, the signature works. The geometry and atmosphere, the architectural stoves that produced the soot that produced the architectural drawings of the stoves. Complex, vividly faceted instinctive compositions, as well as artefacts about life on earth, made of the earth. As the archive opened up, however, many more styles became known: Castle the formalist; Castle the modernist; Castle the designer; Castle the typographer. Scholarship widened. Castle’s first full survey exhibition, James Castle: A Retrospective, curated by Ann Percy at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2008, took in assemblage, isolation, appropriation, repetition, book-making, everything. Castle’s work was getting seen in its entirety, in different contexts. Lynne Cooke’s spectacular Outliers and American Vanguard Art for the National Gallery of Art in D.C. puts Castle on historical record, but it was moments like the Whitney Museum’s 2017 show Where We Are, the first hang in the collections galleries of the new building, that made one feel that Castle had reached the official story of American art.

Installation view, Fabulous Histories: Indigenous Anomalies in American Art, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, October 21–November 19, 2004. Courtesy of Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and artists.

“It occurs to me now that we instinctively wished to spread John’s lessons to others.”

John’s faith in all that Castle could reveal spurred us to think and work flamboyantly. The three of us pitched a group show that refused distinctions between trained and untrained artists to US institutions. It eventually became Fabulous Histories: Indigenous Anomalies in American Art, a show at the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts at Harvard University in the fall of 2004 that hit thematic beats and cast light on artists — among them Castle, Christina Ramberg, Jim Nutt, Martin Ramírez, Jess — some years before the most recent wave of insider-outsider thinking in the art world. John was so proud of this show that he put us up in a suite at the Biltmore Hotel in Providence the night after we gave our curators’ talk. Brendan and I pissed out of the window in hopes of impressing Jina, not for the last time. We really celebrated that night. It occurs to me now that we instinctively wished to spread John’s lessons to others.

Brendan and Jina left for school — they’re now prominent in art and academia, in beautiful callings — and our friend Claire Iltis came in. Claire’s still there, the longtime master designer at the gallery. We did a lot of shows together that went down pretty well, and John rarely asked for sign-off on our increasingly florid press releases. So great was John’s laissez-faire attitude in this department that by 2007 I was writing PR that might use a Trinidadian soca song as a framing device for the exhibition, give a show a title in Danish, or guarantee a giveaway of souvenir bobbleheads of John Ollman at the opening. He let us do whatever we wanted. I told John I wanted to move from Philly while we were eating burgers at the diner in the alley behind the gallery. It had an old-fashioned name. He understood. I took a meeting with Amy Adams a few days later in the nineteenth-floor bar of the Bellevue hotel on South Broad underneath a 3/4-size reproduction of Gilbert Stuart’s The Skater. That’s where Amy’s story with John begins.

I’ll note here that this is just a fraction of John Ollman’s career, a tenth of it in fact. There was a lot of before and a lot of after and it’s still going; this was simply where our lives overlapped. This is just a snapshot. If you have a few minutes, ask John about the ’80s.

John was a figure of considerable mystery, even though we sat alongside him every day. Some things we really knew about him. We knew how he took his Italian hoagie, how much he loved Italian hoagies, how long it took him to do each day of the week of the New York Times crossword puzzle, how he sat when he took extremely long telephone calls at his desk. We knew how delightful it was in his back yard at 10th and Catherine and how much he loved the natural world — John started working for Janet almost immediately after he got an MFA in sculpture, at the climax of which he claims he was most interested in topiary. We knew he vanished to his garden in Maine from Memorial Day to Labor Day; back in South Philadelphia, we frolicked in his garden every night at dusk. We knew he’d return in September with a tan, a cool t-shirt on. Always chill in September. We knew that he was excited to talk to anyone, absolutely anyone, literally the FedEx guy, about the art. When we had a cool thing in the gallery — a particularly sympathetic William Edmondson critter or the 1969 Nutt painting on a window blind or a Forrest Bess or HC Westermann’s Second Shotgun or Martín Ramírez’s Super Chief or a pristine tramp art frame — John could bring the artist, curator, collector, FedEx guy into the energy of this thing. All the way in.

John is very consistent with this energy. We always knew this about him. Perhaps his mystery comes down to his light touch. Let me tease this one out.

John is into books, and he was always aghast when we, recent students of postmodernism, hadn’t seen this or that classic. He’d rustle around the library and dramatically whip out the volume in question, and that’s how we became hip to Flash of the Spirit and Magiciens de la Terre and the Westermann catalogue raisonné. John makes a strong case for having a library.

And it wasn’t just iconic books. Chuck and Jan Rosenak’s Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Folk Art and Artists was always close at hand, the tattered epic in hardback. It was a useful resource for biographical information in our day-to-day research, but it was also a family bible and parlor game. As we flipped through the book, Brendan and I might fall to pieces over, say, Drossos P. Skyllas, a Greek visionary of luminous, banal precision. We would turn to John shrugging our shoulders — who is this guy. He would offer all the additional information, including who he was and what his best paintings were and where they were and exactly how many there were. He had seen them and he remembered them. He was always ready to magnify our interest.

And he still flipped through the roadside auction pamphlets on glossy paper that came in the mail every few months, the mega folk sales with countless face jugs and old objects that wore America like lint. John enjoyed appraising works on the fly, he was intimate with the ebb and flow of thousands of Howard Finster works, he could smell Mose Tolliver paintings, but he also knew about the most marginal figures in the American self-taught art scene. He knew about Benton Wilkens, the artist who exclusively drew pictures of women spanking men with sore red asses that could often be found among the later lots in catalogues from the Slotin auction house in Gainesville, Georgia. We fantasized about showing his work; John chuckled and enjoyed our enthusiasm. He’d seen it all.

John’s example, thus, was to look and remember. Two acts so blunt and basic as to seem trivial, but in fact they’re the foundations of a deep historical understanding of art. See it all. James Castle embodies so much of this, and viewership of James Castle inspires so much of this, and artists and humans who think this way are for sure the community we are still trying to foster around art like this. When we all lead each other through our example, no one is in charge.

![]()

John Ollman and Howard Finster in front of the Janet Fleisher Gallery in 1984 upon the occasion of “Howard and Elijah,” a two artist exhibition with Finster and Elijah Pierce.

“When we had a cool thing in the gallery — a particularly sympathetic William Edmondson critter or the 1969 Nutt painting on a window blind or a Forrest Bess or HC Westermann’s Second Shotgun or Martin Ramirez’s Super Chief or a pristine tramp art frame — John could bring the artist, curator, collector, FedEx guy into the energy of this thing. All the way in.”

John was a figure of considerable mystery, even though we sat alongside him every day. Some things we really knew about him. We knew how he took his Italian hoagie, how much he loved Italian hoagies, how long it took him to do each day of the week of the New York Times crossword puzzle, how he sat when he took extremely long telephone calls at his desk. We knew how delightful it was in his back yard at 10th and Catherine and how much he loved the natural world — John started working for Janet almost immediately after he got an MFA in sculpture, at the climax of which he claims he was most interested in topiary. We knew he vanished to his garden in Maine from Memorial Day to Labor Day; back in South Philadelphia, we frolicked in his garden every night at dusk. We knew he’d return in September with a tan, a cool t-shirt on. Always chill in September. We knew that he was excited to talk to anyone, absolutely anyone, literally the FedEx guy, about the art. When we had a cool thing in the gallery — a particularly sympathetic William Edmondson critter or the 1969 Nutt painting on a window blind or a Forrest Bess or HC Westermann’s Second Shotgun or Martín Ramírez’s Super Chief or a pristine tramp art frame — John could bring the artist, curator, collector, FedEx guy into the energy of this thing. All the way in.

John is very consistent with this energy. We always knew this about him. Perhaps his mystery comes down to his light touch. Let me tease this one out.

John is into books, and he was always aghast when we, recent students of postmodernism, hadn’t seen this or that classic. He’d rustle around the library and dramatically whip out the volume in question, and that’s how we became hip to Flash of the Spirit and Magiciens de la Terre and the Westermann catalogue raisonné. John makes a strong case for having a library.

And it wasn’t just iconic books. Chuck and Jan Rosenak’s Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Folk Art and Artists was always close at hand, the tattered epic in hardback. It was a useful resource for biographical information in our day-to-day research, but it was also a family bible and parlor game. As we flipped through the book, Brendan and I might fall to pieces over, say, Drossos P. Skyllas, a Greek visionary of luminous, banal precision. We would turn to John shrugging our shoulders — who is this guy. He would offer all the additional information, including who he was and what his best paintings were and where they were and exactly how many there were. He had seen them and he remembered them. He was always ready to magnify our interest.

And he still flipped through the roadside auction pamphlets on glossy paper that came in the mail every few months, the mega folk sales with countless face jugs and old objects that wore America like lint. John enjoyed appraising works on the fly, he was intimate with the ebb and flow of thousands of Howard Finster works, he could smell Mose Tolliver paintings, but he also knew about the most marginal figures in the American self-taught art scene. He knew about Benton Wilkens, the artist who exclusively drew pictures of women spanking men with sore red asses that could often be found among the later lots in catalogues from the Slotin auction house in Gainesville, Georgia. We fantasized about showing his work; John chuckled and enjoyed our enthusiasm. He’d seen it all.

“John’s example, thus, was to look and remember. Two acts so blunt and basic as to seem trivial, but in fact they’re the foundations of a deep historical understanding of art. See it all.”

John’s example, thus, was to look and remember. Two acts so blunt and basic as to seem trivial, but in fact they’re the foundations of a deep historical understanding of art. See it all. James Castle embodies so much of this, and viewership of James Castle inspires so much of this, and artists and humans who think this way are for sure the community we are still trying to foster around art like this. When we all lead each other through our example, no one is in charge.

John Ollman and Howard Finster in front of the Janet Fleisher Gallery in 1984 upon the occasion of “Howard and Elijah,” a two artist exhibition with Finster and Elijah Pierce.